How to build a sourdough starter.

First, a bit of knitting for those who aren’t interested in bread…

The Alligator (pronounced ‘amalgamator’ in this household. Don’t ask.) Socks in his chosen yarn, Lorna’s Laces in ‘Forest’. The instep is a twisted rib, basically four rounds k2xp2 rib, then k2t, slip that back onto the left needle, knit the left-most of the original k2 stitches, then put the slipped stitch on the right needle with its new partner. And so forth. Chosen because the twist should tighten the rib a bit (he said the first pair were too loose).

The Alligator (pronounced ‘amalgamator’ in this household. Don’t ask.) Socks in his chosen yarn, Lorna’s Laces in ‘Forest’. The instep is a twisted rib, basically four rounds k2xp2 rib, then k2t, slip that back onto the left needle, knit the left-most of the original k2 stitches, then put the slipped stitch on the right needle with its new partner. And so forth. Chosen because the twist should tighten the rib a bit (he said the first pair were too loose).

And I’d like some advice. I posted a lot of words about design yesterday. I have some photos of a purchased sweater to illustrate some of the points I made (or rather, was shown at the time I bought it). Is it reasonable to post detailed images of design features in a commercial sweater? It’s not a hand-knit, but it is a designer-ish item.

Back to the bread. This isn’t the only way to build a starter, it’s the way I do it. I distrust those whose instructions require organic grapes or yoghurt or potato water and similar. A sourdough starter is a community of bacteria and yeast that feed on the sugars and starches found in wheat and other grains and produce CO2, more sugars and the vast array of other organic molecules that give sourdough bread its distinctive flavour. If you want a community that lives on grain, why add organisms that live on fruit or potatoes? The appropriate yeast and bacteria are in the flour. Speed isn’t important here. If you want fast bread, use commercial instant yeast, which has been bred (ha) to work fast and reliably. Don’t ever add commercial yeast to your starter, it’s not the yeast you’re looking for. If you want speed and reliability in a particular batch of bread, you can (like many commercial sourdough bakers) add it to the dough, or you can use it to make a biga or sponge 24 hours or so before baking. The additional time adds flavour to the dough.

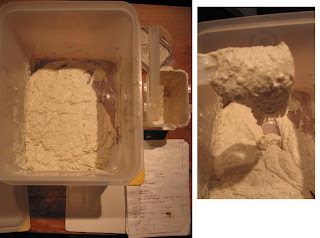

Day One. Everything you need is shown in the photo. Organic rye flour (that’s 1.5kg, the smallest available bag), organic bread flour (from a 25kg bag on the floor), bottled spring water. That’s crucially important: tap water is treated to remove organisms such as yeasts and bacteria, and contains chlorine (amongst other things) to discourage their growth. Put your chosen container on the scale, zero it (I love digital) and add a mix of flours. I used 75g white (you could use brown) and 50g rye (125g total flour). The actual proportion of white/rye don’t really matter, but for some reason bread yeasts love rye, so adding it makes this process easier and faster. I don’t like a strong rye bread so I’ll gradually decrease the amount of rye in the starter as I proceed. The amount of water you add does matter, because that determines the hydration of the starter. Weighing ingredients is more accurate and precise than using cups; if you do use cups, keep a record of everything you do because you must know the proportion of flour to water in the starter when you use it for bread. I make my starters at 100% hydration (this is something called bakers’ percentage*) because it’s easy to work with: equal weights of flour and water. So add 125g of water, stir in well, sniff the result and try to remember what it smells like,

Day One. Everything you need is shown in the photo. Organic rye flour (that’s 1.5kg, the smallest available bag), organic bread flour (from a 25kg bag on the floor), bottled spring water. That’s crucially important: tap water is treated to remove organisms such as yeasts and bacteria, and contains chlorine (amongst other things) to discourage their growth. Put your chosen container on the scale, zero it (I love digital) and add a mix of flours. I used 75g white (you could use brown) and 50g rye (125g total flour). The actual proportion of white/rye don’t really matter, but for some reason bread yeasts love rye, so adding it makes this process easier and faster. I don’t like a strong rye bread so I’ll gradually decrease the amount of rye in the starter as I proceed. The amount of water you add does matter, because that determines the hydration of the starter. Weighing ingredients is more accurate and precise than using cups; if you do use cups, keep a record of everything you do because you must know the proportion of flour to water in the starter when you use it for bread. I make my starters at 100% hydration (this is something called bakers’ percentage*) because it’s easy to work with: equal weights of flour and water. So add 125g of water, stir in well, sniff the result and try to remember what it smells like,

then put the lid on, and leave the container somewhere at cool room temperature. Our kitchen is about 60F, at a guess. A little warmer might speed the process, a little cooler will slow it. Changing temperature might also influence the strains of bacteria and yeast that thrive, but it’s your kitchen they must thrive in.

then put the lid on, and leave the container somewhere at cool room temperature. Our kitchen is about 60F, at a guess. A little warmer might speed the process, a little cooler will slow it. Changing temperature might also influence the strains of bacteria and yeast that thrive, but it’s your kitchen they must thrive in.

Day Two: the next day (time doesn’t matter), check the smell of the batter? dough? stuff, then put roughly half the volume on the compost heap or flush it. Add more flour and water in the same proportion. I usually add about 100g flour (total) and 100g bottled water. There’s the advantage of the 100% hydration: no matter what the weight of the starter, I can always work out the weight of flour and the weight of water in it: just divide the weight of the starter by 2.

I use plastic or wooden spatulas because eventually the starter will be sufficiently acid that, over time, it might etch vulnerable metal. I don’t want metal in my bread!

Day Three: Peer closely at the stuff through the side of the box. Can you see any bubbles? Look carefully at the surface and sniff again. Any sign of bubbles? Does it smell different? If the smell has altered and you can see bubbles, you’ve got a starter. But the process is the same: discard half, add some more food and water.

Day Four: the bubbles are large enough to photograph through the side of the container, and you can clearly see them on the surface. The starter definitely smells… ‘different’ is the kindest word. It’s not appetising, at least not to me, but it’s very young. Discard half, add more flour and bottled water (always, always bottled water) and put back in its place. Just for reference, here’s the surface of my own starter, which is several months old now, at the same stage after feeding:

Day Four: the bubbles are large enough to photograph through the side of the container, and you can clearly see them on the surface. The starter definitely smells… ‘different’ is the kindest word. It’s not appetising, at least not to me, but it’s very young. Discard half, add more flour and bottled water (always, always bottled water) and put back in its place. Just for reference, here’s the surface of my own starter, which is several months old now, at the same stage after feeding:

It smells almost fruity, a rich, complex scent full of aldehydes and ketones. There’s a hint of acidity, but this is not and never will be the vinegar-scented ‘San Francisco’ sourdough. Many people have wasted a lot of money trying to duplicate the conditions for that. What you will get will be your own local bread. A. brought me a loaf of SF sourdough from his last trip to the city: the bag smelt so ridiculously strongly of acetic acid I thought at first he’d brought me salt-and-vinegar crisps/chips. But the bread didn’t taste of it and (frankly) I thought mine was just as good. Down, ego, down!

It smells almost fruity, a rich, complex scent full of aldehydes and ketones. There’s a hint of acidity, but this is not and never will be the vinegar-scented ‘San Francisco’ sourdough. Many people have wasted a lot of money trying to duplicate the conditions for that. What you will get will be your own local bread. A. brought me a loaf of SF sourdough from his last trip to the city: the bag smelt so ridiculously strongly of acetic acid I thought at first he’d brought me salt-and-vinegar crisps/chips. But the bread didn’t taste of it and (frankly) I thought mine was just as good. Down, ego, down!

Today is Day Six. There are more bubbles visible, and the smell is slightly more attractive. I’ve just done the discard/feed and I will continue to repeat the process for the next few days with a view to using this for a batch of bread on the weekend.

Today is Day Six. There are more bubbles visible, and the smell is slightly more attractive. I’ve just done the discard/feed and I will continue to repeat the process for the next few days with a view to using this for a batch of bread on the weekend.

I took a bread-making weekend course a couple of years ago, primarily for the chance to fire and bake in a wood-fired oven. It was fascinating. But I also saw how a commercial baker maintains his/her starter. Starters. A litre or more of each in different stages of development, some full rye, others a mix of flours. We discussed the financial cost of this for home bakers, something he hadn’t considered. For most of us, the discarded flour and bottled water (he had spring water on tap!) adds up to considerable expense over time. There are two solutions. One is to build a new starter whenever I want to bake sourdough. Plan a week or more in advance? No chance. The other, which he didn’t like but agreed was feasible, is to keep your starter in the fridge for most of its life. Once you’ve got a healthy starter you can feed and water it, allow it to work for a couple of hours, then put it in the refridgerator. This slows the action of the bacteria and yeasts so you can feed and water it less often. Mine lives in there for four or five days at a time: two days before I want to use it, I take it out, discard half, feed and water it and leave it at room temperature to become fully active. Before going to bed I’ll feed and water it again (no discard), and I’ll do that again the next morning to build the volume I need for baking. After I’ve taken what I need, I feed and water the remainder, let it work a couple of hours, then put it back in the refridgerator. This undoubtedly changes the species composition of the starter, but as long as it works, I don’t mind.

For bread-making you’ll need a plastic or ceramic container holding at least 5-6 litres don’t tell anyone, but I used a (clean) washing-up bowl when I started. Not a new one, I wanted to be certain that any peculiar volatiles in hte plastic had leached into the washing-up water. Your life will be made much, much easier if you also have a dough scraper. Mine looks like the Nisbets one, but it’s mild steel rather than plastic. I have no idea whether that King Arthur one works on bread dough! Sheets of non-stick baking parchment are also really, really useful. For the best possible bread, you’ll need a baking stone or something similar in the oven to provide bottom heat. I have a slab of kiln shelf c. 15mm cut to fit my oven shelf (allow a gap all round for air circulation). Other people lay (clean!) ceramic floor tiles to almost fill an oven shelf. If you use baking parchment the bread won’t be in contact with the tiles. I know of one person who used an entire concrete paving slab. I think there’s something about this in the RFS FAQ, too.

* that link takes you to the rec.food.sourdough FAQ. rfs is a Usenet group, which you can read using a dedicated newsreader or via Google groups, and it’s a fabulous resource for people who want to bake really, really good sourdough breads. Or any other stuff, for that matter. Just check the FAQ for answers to any question you might have before posting to the group: they put an incredible amount of time and effort into compiling that resource.

Day One, 1830. All the ingredients neatly laid out with my bread notebook, full of scribbled calculations for different weights of doughs of differing hydrations (some so wet they slithered off the oven shelf). The completed sponge (starter plus flour and water) is on the right, to show the texture.

Day One, 1830. All the ingredients neatly laid out with my bread notebook, full of scribbled calculations for different weights of doughs of differing hydrations (some so wet they slithered off the oven shelf). The completed sponge (starter plus flour and water) is on the right, to show the texture.