Over the last few weeks several people have asked a FB spinning group about spinning cotton wool/cotton balls – the things sold for makeup removal – as a cheap, easy to find version of cotton. I said cotton balls aren’t like REAL cotton; they’re made of heavily-processed waste fibres so they won’t make a lovely even yarn but I do enjoy spinning them. I discovered I didn’t have any when I looked for the bag in the stash to take a picture. My local supermarket (this is the UK) also didn’t have any so I added a bag of 100% cotton balls to the Amazon basket.

Can you read the label? It looks like the label on the Amazon website but there are different words: ‘Vacuum packed to reduce packaging size’. Cotton isn’t elastic, it doesn’t rebound to its original shape in the way that wool does. The label claims the cotton balls will expand after the pack is opened, but that seems extremely unlikely.

What to do? I can’t send the stuff back, I’ve opened the pack.

Was this decent cotton before it was abused?

No, and I didn’t expect that it would be. Cotton balls are a way of making money from waste fibre. In the photo below the top fibre is cotton sliver (technical term for the cotton version of what spinners know as wool top) opened to show fibre alignment and nepps. Fibre below it is one of the cotton balls.

Rehabilitating bad cotton

First thing is to encourage the cotton to rebound and expand as much as it can. Heat and moisture help, so I put the balls in a colander over a bowl of steaming water and left it overnight, mixing top to bottom a few times before I went to bed.

That helped but not much. I tried Extreme Steam at the spout of a boiling kettle; do this with real cotton sliver and you can actually see it expand; this, not so much.

Oh well.

How can I prep this for spinning?

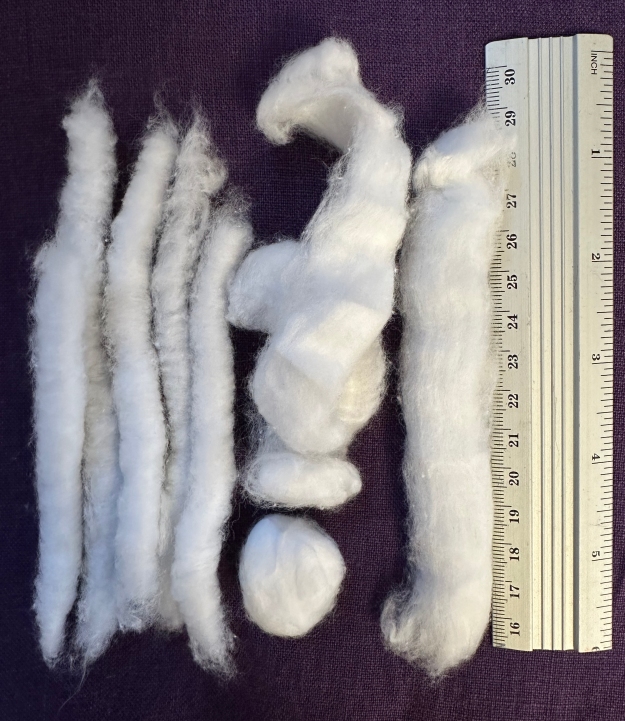

The three obvious options are shown in the photo below.

Centre, one of the cotton balls and above it, a couple of the balls unfolded to show the firmly set creases, a truly awful thing to see in cotton, each compacted area will be a difficult or undraftable slub in the yarn. But I can spin this.

To the right, next to the ruler, one of the balls unfolded and then carefully passed through steam from the kettle, allowed to rest, then steamed and rested again. The creases are still visible but it’s an improvement.

At left, five punis. Each is 2 1/2 (3 was too much, 2 seemed ungenerous) cotton balls unrolled and carded on my small Clemes & Clemes handcards. I don’t doff all the fibre onto one card at the end; instead I use a fine knitting needle to roll the fibre off each card, then slide the rolled fibre off. Moisten the needle with just the right amount of spit to catch the fibres at the start of the roll.

There wasn’t a lot of difference between spinning the unfolded fibre and the steamed unfolded fibre. Spinning with the tahkli (a support spindle with high speed good for spinning fine fibres) yielded a finer yarn but dealing with the slubs was more fiddly than spinning on the Majacraft Rose; both methods yielded a good somewhat slubby singles that plied up nicely.

Carding the cotton for the punis opens and rearranges the fibres, so I’d hoped they would draft more easily even if the yarn was still slubby. They did, but not in a good way. The cotton drafted easily into a succession of long slubs that, when double-drafted for a competent yarn tended to snap in the thin sections between the slubs. My theory is that the additional carding, even if only 2 brushes of the cards to spread the fibre evenly, did too much damage: too many of the fibres had been weakened or shortened.

Verdict

I’d spin this from unfolded balls, steamed once or twice and allowed to rest before I spin them. Why bother? Because the end result is a good and interesting yarn.

On the left, tahkli-spun; on the right, wheel-spun. Both are competent. The really fluffy bits of the wheel-spun are the puni slubs; these will probably shed fibre and pill even if a weave structure locks the fibres into place, and they might fail under warp tension. So if I was spinning this for use in knitting or weaving I’d avoid slubs this large and loose.

Best way to do that is buy nicer cotton balls, avoiding ones that have been vacuum-packed. The ones I bought from Superdrug in Canada were lovely.

The fibre: a slightly darker version of the Wensleydale top, together with a washed lock from a Wensleydale fleece. Shiny!

The fibre: a slightly darker version of the Wensleydale top, together with a washed lock from a Wensleydale fleece. Shiny! The singles, before and after steaming to set the twist.

The singles, before and after steaming to set the twist. The sized singles yarns drying on the clothes tree. The plastic bin is weighted with just enough water to hold the singles taut, removing the pigtails, but with minimal stretching. Remember that wet wool is weaker than dry wool.

The sized singles yarns drying on the clothes tree. The plastic bin is weighted with just enough water to hold the singles taut, removing the pigtails, but with minimal stretching. Remember that wet wool is weaker than dry wool.

Unsurprisingly the weft stripe is more obvious on one side, the warp stripe on the other, but the chequerboard is visible on either side if the light is right.

Unsurprisingly the weft stripe is more obvious on one side, the warp stripe on the other, but the chequerboard is visible on either side if the light is right.