Or, in Old Norse, vaðmál.

From vað (stuff/cloth) mál, (a measure), because this fabric was a household standard and trade staple in Scandinavia, Iceland and Greenland where wool from local sheep was the primary textile fibre. Know to have been in production from at least the 11th century to the 17th century, pieces of vaðmál meeting strict standards for length, width and quality were legal currency in Iceland and sometimes elsewhere. The definition of the Icelandic ell, the unit of measure, changed over time, possibly as a result of increasing trade with England where vaðmál imports supplied coarse cloths. Elsewhere in northern Europe the definition of ‘watmal‘ or ‘wadmal‘ was broader: a coarse cloth worn only by those who could not afford better. Textiles found in the graves of 14th-century Herjolfsnaes in southern Greenland by Poul Norlund’s 1921 expedition provide a wealth of information about local production of vaðmál and how the garments of that time were constructed.

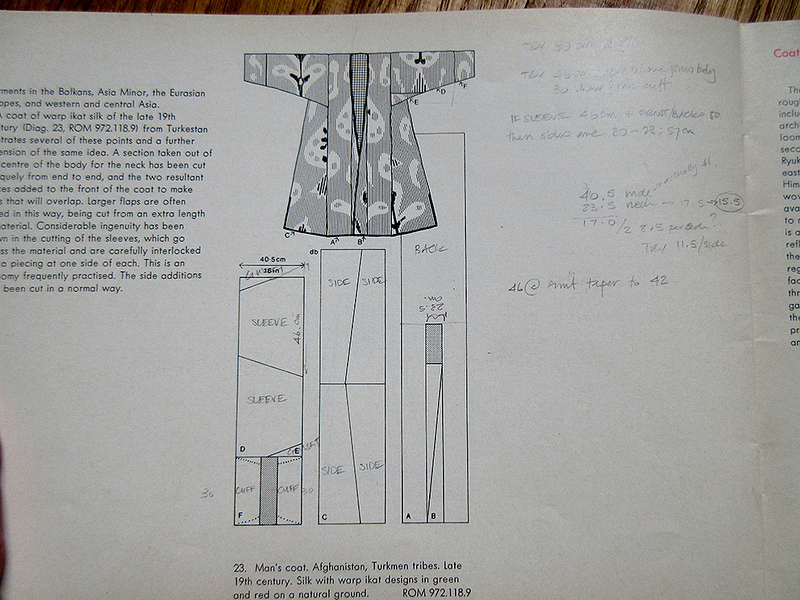

The finds from Herjolfsnaes and other sites in Greenland are beautifully documented in two modern volumes, Else Østergård’s Woven into the Earth, which includes a detailed description of the vaðmál fabrics, and Medieval Garments Reconstructed with even more information about how to spin the yarn to weave vaðmál fabric to make copies of the garments. I’ve had vaðmál on my mind for a long time so, when Kate Larson of Long Thread Media asked me to write an article for Piecework magazine about stitches from Norse Greenland (published in the Summer 2020 issue of Piecework) and how I’d adapted one of them to solve a problem I created for myself, I spent only one evening playing with wool and modern fabric before concluding that I needed to know how these stitches worked on the original vaðmál.

Icelandic sheep in Iceland, Diego Delso on Wikimedia Commons

Vaðmál is the best example I know of people making the best use of the fibre produced by their local sheep, which from raw wool found in Greenland resembled the modern Icelandic breed. These hardy sheep are double-coated, with an outer coat (the tog) of long hair protecting the inner wool (the thel) from harsh weather. The hairs were removed from the fleece with wool combs, then further processed by combing to be spun for warp. The softer wool was opened up loosely into a cloud of fibre and spun for weft. The Norse women would probably have plucked the wool from sheep rooing (shedding their fleece naturally) as primitive breeds do; few modern shepherds can do that, so my fleece was shorn. Many shepherds in North American shear twice a year and discard the winter fleece, full of straw and hay, but I was lucky enough to find a ram fleece with a full year’s growth.

Washed Icelandic fleece, 12 months growth. The long outer hair is darker than the softer wool.

I pulled the long hairs out of each lock (I find this easier) and lashed them onto my wool combs.

One of the pair of combs with locks lashed on, ready for combing, plus a handful of the wool remaining once the hair has been removed. Note the difference in colour.

Two transfers removed most of the unwanted short fibres, skin flakes and vegetation.

The combed hair ready to be pulled off the combs. The comb is held down; the loose end of the ‘pony tail’ is pulled gently through a small hole in a diz. Done carefully, friction ensures that all the fibres flow through the hole to become a long loose rope of fibre ready for spinning.

The end result was a lovely length of top, but rather coarse and stiff by comparison with the Wensleydale and Cotswold long wools I usually comb.

Bottom: the long combed hair ready for spinning. Above: the short waste fibre and other material removed by the combing process.

I decided to lightly card the thel and spin from rolags because time was short. This wasn’t the focus of the article, after all!

The warp yarn was a z-twist singles (unplied yarn), hardspun (twist angle of 40°–50°), roughly 1mm thick. The Norse settlers would have spun it on spindles; wheels are faster by the hour, I have wheels and I know how to use them. The coarse fibres created a characterful yarn, somewhat prickly and reluctant to flex. The weft included both down (very short soft fibres from the base of the fleece) and slightly longer wool; spun long draw this blend of lengths tends to create a textured yarn as the longer wool fibres can twist-lock either side of a slub that as a result has to be persuaded to draft down to the desired grist.

I used a strong gelatine size on the warp but the gelatine did not stick as tightly to the coarse, shiny hairs as I had hoped. It did little to lock the stiff ends of the hairs into the yarn, which meant more friction between the yarn and the heddles and reed. Which in turn emphasized any unevenness in the yarn. The cassimere merino yarn was much easier to weave,

As I wove I was able to feel the fabric developing, understand how the softer weft beats down to almost cover the coarse, hairy warp. The fleece from THIS sheep would never have been dress fabric — it is too coarse — but it could easily have been outerwear, still a garment, when I’d thought that warp would have been best made into rope.

Not my best weaving, but proof of principle is all I really needed.

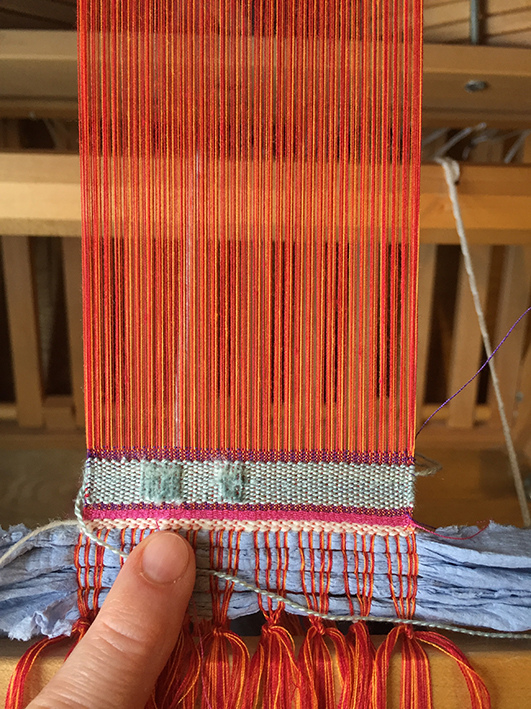

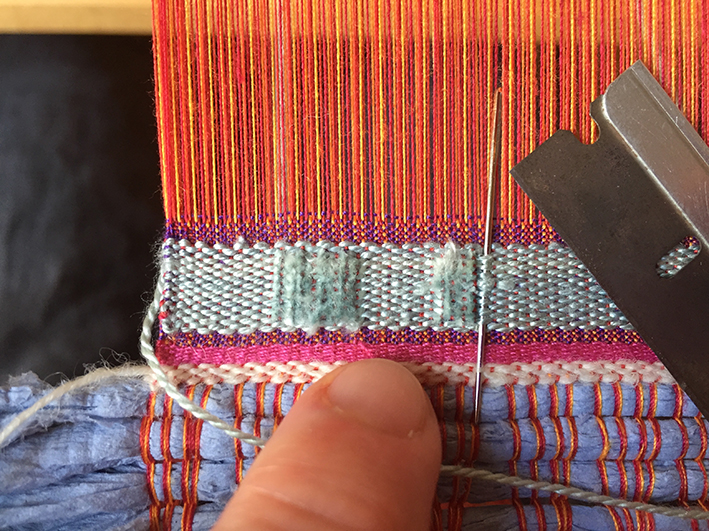

I cut the fabric off the loom and began to test seam and edge finishes sewn with reserved warp thread. Woven into the Earth suggests that the longest and, finest tog was reserved to be spun into thread, and I now understand why: stiff thread with many protruding stiff fibre ends DOES NOT lend itself to easy tidy sewing. Nonetheless I persevered. I singled some cut edges, stabilizing them by binding the weft threads with thread running into and out of the fabric (see the article for more information about this technique). I wanted to demonstrate the way tablet-weaving was used to bind and protect hems and other ‘edges’ subject to heavy wear, so I ran a short warp of the warp threads on my small tablet-weaving loom (with thanks to John Mullarkey for this lovely little loom).

If you are familiar with tablet-weaving you may be able to understand how this works from the photograph. In short, the tablet warp is held close to what will be the outer/visible surface of the fabric. Shorter lengths of weft are threaded into a needle; after passing through the shed the needle-with-weft is taken to the back of the fabric then — the point where this photo was taken — brought back through the fabric ready for another pass after the tablets are rotated to change the shed. The band is sewn to the surface of the fabric as part of the weaving process. It’s a bit tricky to work out the spacing of the weft passes to make the band lie flat on the fabric, but practice makes perfect.

The end result! Tiny vaðmál!

With Norse seams. The Norse women alive 600 years ago live again as my hands learn from the work of their hands.

Women’s work.

The vaðmál itself is a fascinating fabric and I am slowly processing a much nicer, much softer double-coated Shetland lamb fleece to make a larger sample that might, if I’m lucky, be large enough to be a waistcoat.

Indigo-dyed handspun cotton singles drying on the rosemary bush by the kitchen door. I miss that bush, and our North Ronaldsay sky-blue doors.

Indigo-dyed handspun cotton singles drying on the rosemary bush by the kitchen door. I miss that bush, and our North Ronaldsay sky-blue doors. I had to finish drying the yarns on the radiator. Hmm. Clearly I dyed silk fibre, too. I wonder where that is? In one of the many boxes, of course.

I had to finish drying the yarns on the radiator. Hmm. Clearly I dyed silk fibre, too. I wonder where that is? In one of the many boxes, of course. The gelatin-sized yarns drying under light tension – those water bottles are not full! – suspended between the hoe and an old rake handle wrapped in clingfilm aka Saran wrap on the clothes tree. The old grey lunchbag contains clothes pegs.

The gelatin-sized yarns drying under light tension – those water bottles are not full! – suspended between the hoe and an old rake handle wrapped in clingfilm aka Saran wrap on the clothes tree. The old grey lunchbag contains clothes pegs.

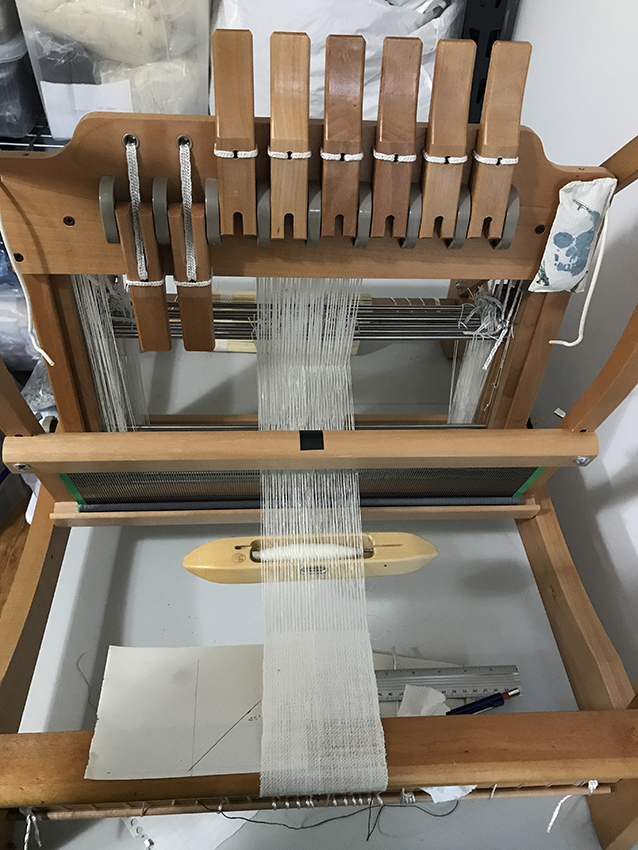

I have started weaving some fine yarns with the lease sticks in place. Like back-to-front or front-to-back warping, lease sticks in or out is something weavers seem to choose as habit early in their careers. I didn’t like the lease sticks in when weaving thicker, fuzzy yarns: my impression was that the sticks were encouraging fuzziness and binding of threads in the warp. But feeding firmly sized, finer yarns through the even tension of the lease sticks seems to correct some of my warping issues.

I have started weaving some fine yarns with the lease sticks in place. Like back-to-front or front-to-back warping, lease sticks in or out is something weavers seem to choose as habit early in their careers. I didn’t like the lease sticks in when weaving thicker, fuzzy yarns: my impression was that the sticks were encouraging fuzziness and binding of threads in the warp. But feeding firmly sized, finer yarns through the even tension of the lease sticks seems to correct some of my warping issues.

The fibre: a slightly darker version of the Wensleydale top, together with a washed lock from a Wensleydale fleece. Shiny!

The fibre: a slightly darker version of the Wensleydale top, together with a washed lock from a Wensleydale fleece. Shiny! The singles, before and after steaming to set the twist.

The singles, before and after steaming to set the twist. The sized singles yarns drying on the clothes tree. The plastic bin is weighted with just enough water to hold the singles taut, removing the pigtails, but with minimal stretching. Remember that wet wool is weaker than dry wool.

The sized singles yarns drying on the clothes tree. The plastic bin is weighted with just enough water to hold the singles taut, removing the pigtails, but with minimal stretching. Remember that wet wool is weaker than dry wool.

Unsurprisingly the weft stripe is more obvious on one side, the warp stripe on the other, but the chequerboard is visible on either side if the light is right.

Unsurprisingly the weft stripe is more obvious on one side, the warp stripe on the other, but the chequerboard is visible on either side if the light is right.

Wearing The Hat in public for the first time, hiking in Derbyshire.

Wearing The Hat in public for the first time, hiking in Derbyshire.