This is what started it all. Spin Off Autumn Retreat 2010. A pile of dyed mulberry silk top and some felt discs on a table in Robin Russo’s class, and the comment that spinning your own silk embroidery thread and stitching a needle case is good fun. So I spun the silk using a top-whorl spindle to insert quite a lot of twist, used an Andean plying bracelet for the short lengths I spun, and used the embroidery stitches I could remember from my childhood. It was good fun. And that was my first gentle reminder that stitching could indeed be fun.

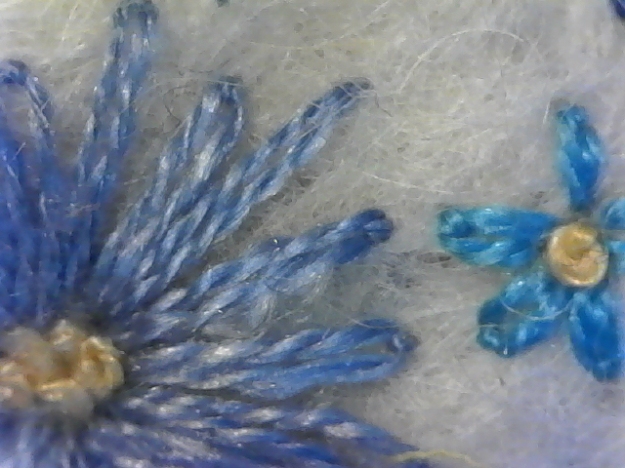

The face of the needle case embroidered with 2-ply handspun mulberry silk top in 2010.

The face of the needle case embroidered with 2-ply handspun mulberry silk top in 2010.

I’ve used this needle case gently for the last 11 years and the silk threads are still in reasonably good shape.

You may be able to see some slight ‘fuzziness’ indicating wear on the areas with very little twist.

Twist is good!

Twist locks the fibres in the yarn together to make a competent yarn: too little twist allows the fibres to slide within the yarn, which will then stretch under tension or even drift apart entirely (don’t ask me how I know this, it’s not a pleasant memory). But tight twist also means the fibres tightly spiralling on the thread are less exposed to wear in any one location on that thread. Tight twist locks the ends of fibres more tightly into the spun yarn.

But not always!

Uncountered twist makes a yarn — or in this case a thread — that is lively. Most stitchers either add twist or untwist their thread ever-so-slightly with every stitch; if you add twist, you’ll know it because your thread starts tying itself in knots. A lot of twist results in a thread that may not flatten and spread to cover the underlying fabric. It might even stay entirely round, which is good if you’re couching it down, not so good for satin stitch. Like cotton, silk can take a lot of twist before it becomes wire: on average, when in doubt, always add a little more twist to silk.

Choose a yarn structure: sample silk threads

I learn a lot by looking at and handling examples of things to understand how they behave.

In the image below silk threads are shown at 250x; they’re all from the same shot, split to allow me to name them. The white line indicates a 45° angle. [I’ve spelt ‘Gutermann’ incorrectly: it should be Gütermann. Sorry.]

Using a needle to unpick the thread and a jeweller’s loupe to see the result I can say the first three (1,2, and 3 in case of doubt) are all 3-ply threads. 4, the embroidery floss, is 2-ply. Why? 3-ply yarns are almost circular in cross-section, so they look much the same diameter regardless of how they lie on the fabric, whereas 2-ply yarn is roughly oval in cross-section: it has a flatter, wider side and a narrower side.

So a 3-ply sewing thread will make a more uniform line of stitches, and being circular and tightly-spun might even move more smoothly through the fabric. The 3-ply Sajou and Soie Perlée stand cylindrical, high and glossy above a ground fabric or other stitches to catch the light and provide structure to a design.

By contrast the 2-ply embroidery floss will lie relatively flat on its flat side and because it is relatively loosely plied (compare the twist angle) it will spread even flatter to cover more of the ground fabric.

5, the 2-ply handspun silk top, is almost as tightly spun as the commercial threads, it’s just a bit thicker. It’s relatively ‘fuzzy’ with a halo of ends around the thread by comparison with the spun reeled silks above it, but that is not proof that they are reeled and the handspun is spun from silk top: heat is used to burn that fuzzy halo off yarns mill-spun from silk top.

6 I will explain a little later.

Other factors to consider

Sewing thread and most embroidery threads (leaving aside those attached to the fabric by other threads) have to pass through a fabric multiple times. Fabric is hard on thread. Every slub will catch on the fabric, the leading edge of the slub will abrade more and fray and eventually fail. The slub will enlarge the hole made by the needle, damaging the fabric and leaving the rest of the thread a bit loose in that large hole.

So unless you want texture and are happy to live with the consequences, spin consistent singles and ply consistently. You don’t need a lot of silk to make a lot of thread, so buy the best quality silk you can find. Avoid clumps of short fibres, neps, noils and other annoyances if you can, otherwise pick them out of the fibre as you spin. Or accept the consequences: it’s unlikely to be fatal or even a disaster! Uneven silk thread works well in rustic textiles sewn in the boro tradition, even in relatively precise geometric figures.

There is significant variation in thread thickness and the amount of twist. Not my best spinning, but mottanai applies here: use what you have, waste nothing.

And it looks perfect appropriate, at least to me.

I have an example of silk embroidery in my historic textiles collection.

This is probably an envelope case to hold visiting cards c. 1720 (dated by the style of embroidery). Undyed linen (note that there are two layers, the outer being a much finer weave) hand-sewn and embroidered with yellow silk.

A slightly closer view of the embroidery including a view of the back because embroiderers always like to see the reverse. The flowers and other details are back stitch, with a simple wrap binding the edges of the envelope. The insert detail shows more clearly the sheen of the silk – after 300 years! – and the structure of the yarn, which is a 2-ply twisted floss.

And that’s why I tried Number 6 in the photo above, quickly twisting together a couple of strands of silk floss from Pipers Silks in the UK. It works, would work better if I used more strands for a thicker thread. But I’m not going to do that: I want to use that silk as it comes because it is so very beautiful and so very, very challenging.

I hope that’s enough to get you started. Use the best silk you have, spin evenly, spin reasonably tightly if not very tightly, it’s good fun!