This is complicated and far easier to explain in person when I’m pointing at the bits of your wheel in front of you, but I’ll try to cover the main topics, and I’ll suggest some tweaks that I find useful.

If you find this an intimidatingly technical read, I assure you it was just as intimidating to write. It requires precision in the descriptions that makes me feel as though I’m pretending to be an engineer.

‘how do I stop my wheel pulling!’ is the most frequent question when I teach this in person, so I’ll start by discussing take-up (the speed/force with which your wheel pulls the yarn through the orifice and onto the bobbin).

‘how do I add more twist faster?’ Once your wheel isn’t snatching the yarn from your hands you have time to consider another important issue: the thinner your yarn, the more twist is needed to make it competent. So, once you’re happy drafting your fine yarn it’s worth setting up your wheel to add lots of twist fast if that’s possible.

Here’s an example of what is possible with a wheel set up to spin fine thread. At Fibre East in 2014 someone asked if I could spin cotton thread for lacemaking. I said I wasn’t sure, never having seen any. I went home, ordered some 185/2, and experimented. The answer is yes, I can (the thread on my bobbin is 2-ply), but I cannot mercerize the thread so it’s too fuzzy and not shiny enough.

Definitions referred to in the text

Fat-core bobbin: a bobbin that is made with a fatter-than-usual central tube connecting the two ends. You can make a fat-core bobbin by half-filling any bobbin evenly with random yarn, then wrapping a piece of paper around the yarn to give a smooth starting surface. Or just hold a strip of card onto the yarn for a couple of rotations. Or buy some foam pipe insulation with a central hole that roughly fits the tube of your bobbin. I like to have a different (smooth) surface in case my fine yarn starts to sink into the previous yarn, plus I can admire the new fine yarn more easily.

Lacing or cross-lacing a flyer: taking the yarn (or the leader, to start with) from the bobbin to a hook on one arm of the flyer, then back to a hook on the other arm [repeat as desired] before taking it to the orifice and out into the world. Each additional hook creates friction that reduces the take-up slightly. You can lace any flyer with hooks. If the one set of hooks is on the other side of the flyer arm I have been told you can put the yarn through a hook, take it under the flyer to a hook on the other side, then back again, but I have not tried this myself. Note that lacing will reduce the amount of yarn you can put on the bobbin: don’t fill to the point that the bobbin is rubbing against the laced yarn.

The ratio of a wheel is the number of times the flyer rotates for each rotation of the drive wheel. The higher the ratio, the more rotations of the flyer. The current Ashford Traditional set up as ‘single drive’ (I think that’s scotch tension) has a maximum ratio of 17:1, which means the flyer rotates 17 times for each rotation of the drive wheel. This is faster than the maximum possible for a normal Lendrum with a top ratio of 10:1. If that is far too slow, then just swap the standard Lendrum flyer for the Lendrum Very Fast Flyer with tiny flyer whorls for a maximum ratio of 44:1 (44 rotations of the flyer for each rotation of the drive wheel).

Take-up: the force with which yarn is pulled onto the bobbin. The flyer of a spinning wheel winds yarn onto the bobbin because the flyer and the bobbin rotate at different speeds. The greater the difference between the bobbin speed of rotation and the flyer speed of rotation, the harder/stronger/faster the take-up will be. The harder/faster the take-up, the faster the yarn is pulled onto the bobbin. Which means less time for you to draft a fine, even yarn, and less time for twist to be added to it before it goes onto the bobbin (the finer the yarn, the more twist is needed to make it competent). All of which means that if you are trying to spin finer yarns, especially weaving yarns or threads, you need to understand how to make sure you can keep the yarn off the bobbin long enough to add enough twist to make that yarn competent.

‘How do I stop my wheel pulling so hard!’

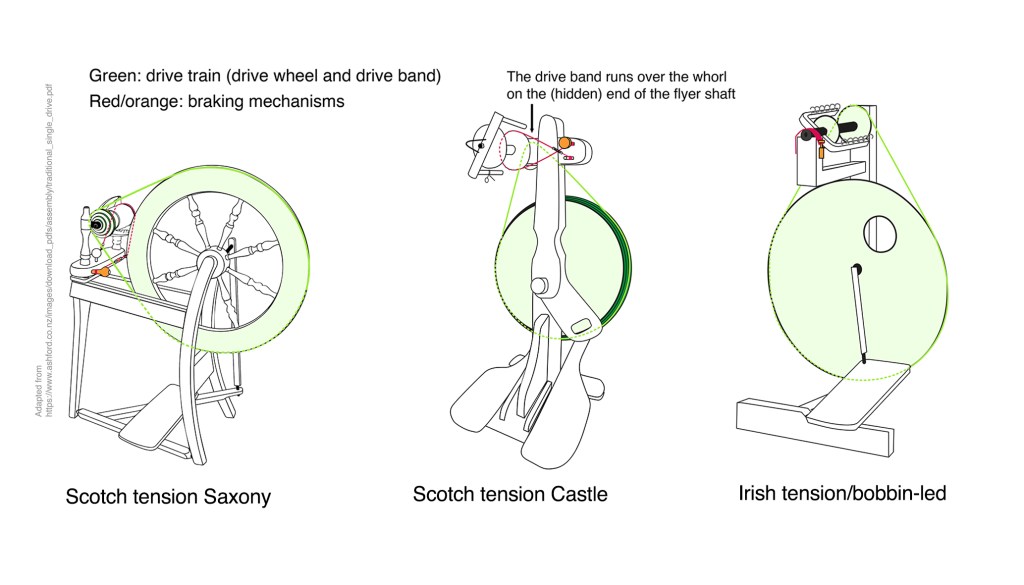

Spinning wheels may be classified according to the way they transfer rotation from the drive wheel to the flyer and the bobbin (in other words, which bits are connected by the drive band). The different ways of transferring rotation mean different ways to control take-up (see the definition above). Here are some suggestions for ways to reduce take-up on different wheels.

On a double drive wheel (not shown in the diagram, I ran out of time!) the drive band forms a figure-of-eight folded back on itself to become two loops. One of those loops goes around the flyer whorl to drive the flyer, the other goes around the bobbin, and then both loops go around the drive wheel. The main control of speed and take-up (the power with which the yarn is pulled onto the bobbin) is slippage, the loss of power caused by the drive band sliding around the whorls instead of making the whorls spin. Thus you can reduce take-up by loosening the drive band (usually by tilting or sliding the mother-of-all toward the drive wheel) to increase slippage. If you want super-fine control consider using a thin, hard-spun drive band such as fine crochet cotton. It is sometimes said that there is a relationship between drive band thickness and the thickness of the yarn you are spinning: thinner and/or harder drive bands have a smaller surface area in contact with the flyer whorl, so finer adjustments may be possible.

Scotch tension wheels

the drive band connects the drive wheel to the flyer

The flyer begins to rotate and the rotating shaft of the flyer drags the bobbin with it, meaning a more gentle start. As the bobbin fills it gets heavier, which means it isn’t slowed so much by the brake band. You might need to tighten the brake band a tiny bit to maintain take-up as the bobbin fills.

To reduce take-up start by loosening the brake band (turn the appropriate knob). You can also lace the flyer and/or use a fat-core bobbin, but Scotch tension offers yet another option: you can change your brake band.

A finer/thinner brake band offers finer control because it has a smaller surface applying friction. I use a fine crochet or tatting cotton for my brake bands. I recommend trying this particularly if you are currently using a monofilament (clear plastic fishing line) brake band. You don’t have to cut or otherwise destroy your existing band, just untie it (even if it’s fiddly) and try something thinner. You can always put the old one back.

Another issue I’ve seen on some wheels is that the spring fitted on the brake band can be too stiff to ‘even out’ tiny differences in take-up. If you’re having no trouble drafting a fine competent yarn but it sometimes breaks for no obvious reason, consider this possibility. I have made improvements by swapping out both Ashford and Majacraft factory springs for softer springs; rubber bands work very well but don’t last long, hair elastics last longer (you can cut and knot long ones to make them fit). I’m currently trialling the spring from a cheap pen on the Majacraft and so far I like it.

Irish tension or bobbin-led wheels

the drive band connects the drive wheel to the bobbin

Wheels such as the Louet S10 transfer rotation directly from the drive wheel to the bobbin. This means the bobbin is the first thing that rotates (hence the name ‘bobbin-led’) before friction between the bobbin and the shaft of the flyer basically drags the flyer into rotating. So on these wheels the bobbin moves first and it moves fastest, which means it starts with a strong ‘tug’ on the yarn you are spinning. They were designed to spin flax which has a long, strong fibre; wools and cottons have shorter, weaker fibres so fine yarns spun from these are more easily broken by that initial tug.

To reduce take-up and the strength of that initial tug, after loosening the brake with the screw (you can have it so loose that the brake is just sitting loose on the orifice) try any or all of the following: make sure everything is lubricated so the flyer starts moving as quickly as possible; lace the flyer; use a fat-core bobbin.

‘how do I add more twist faster?’

Not all wheels allow you to do this. On some wheels you will have to sit and hold the yarn and treadle until the yarn has enough twist for your needs and you can allow it flow onto the bobbin.

Note: ALWAYS check the amount of twist by examining the yarn on the bobbin. Frictional contact with everything on the route from your hands to the bobbin – the edge of the orifice, the hooks – holds twist back, so there’s more twist in the make between your hands and the orifice than there is in the yarn on the bobbin. You can and should check this for yourself: pull a loop off the bobbin and allow it to ply back on itself, then allow the yarn outside the orifice to do the same thing. The loop outside the orifice will have a slightly tighter twist. So you need to treadle until you like the yarn coming from your hands, then treadle a little bit more to ensure the yarn on the bobbin has the same twist.

Some wheels allow you to alter the speed at which the bobbin and flyer rotate in relation to the drive wheel (the wheel’s ratio), and this allows you to add more twist faster with the same treadling speed*. For example, if the whorl on your flyer has more than one groove, putting the drive band around the largest whorl means the flyer will rotate fewer times per rotation of the drive wheel than if you put the drive band around the smallest whorl. I can’t think of a better way to say that in words. But if it doesn’t make sense, mark a distance on your (flat) floor; 18″ will suffice. Make a mark on a can of tomatoes, then count the number of times that mark comes around as you roll the can the 18″. Now mark and roll something smaller (a pill bottle, or a pencil) the same distance and count in the same way. The smaller thing rotated more times over the same distance because it has a smaller circumference (my primary school teacher would be so proud…). Which is why using a smaller whorl means your flyer and bobbin rotate more times (inserting more twist) per rotation of the drive wheel. ‘Large drives small’ for maximum rotation.

Some wheels also have whorls on the drive wheel, which allows more variation in the ratio. Using the largest whorl on the drive wheel to drive the smallest whorl on the flyer means the flyer is rotating as many times as possible for each rotation of the drive wheel. On Majacraft wheels where the flyer whorl is easily accessible, sticking out above the drive wheel, it is easy to use different flyer whorls to insert more or less twist, or even to add a third whorl between drive wheel and flyer to further accelerate rotation.

*Note ‘same treadling speed’, not same effort. Nothing is free: the extra rotation/twist requires a little more treadling effort to do the work (of rotating the flyer and bobbin faster).

The photo below shows the back of my Majacraft Rose, with the drive band coming from the largest whorl on the drive wheel to the smallest whorl of the high-speed flyer whorl. This is the ‘accelerator’ or ‘high speed’ head for the Rose; the large whorl to the right can be used to further increase the rotational speed of the flyer and bobbin: run the drive band to the small whorl of the accelerator bobbin to make it rotate as fast as possible, then run the accelerator band (not shown in this photo) from the large whorl of the accelerator to the small flyer (you might notice that to do this I have to reverse the position of the flyer whorl). The grease pencil notations are for calculation of ratios in various configurations.

Here’s a reward for reading all the way to the end. Scotland! looking north from ‘The Devil’s Staircase’ (not as bad as it sounds, Conic Hill was far worse) on the West Highland Way.