Is one extremely long post once a month equivalent to four much shorter posts? That’s not a real question! Honestly, if I had more time I’d post more often, but it does take quite a lot of time to write this much. Perhaps I should try limiting myself to 140 characters :-)

Anyway. His ankles are still not allowed to walk, so last Saturday he cycled 80k while I walked 13.7 miles. More accurately, he cycled, showered, painted the shelves, ate lunch, then sat and relaxed while I walked 13.7 miles. 5 1/2 hours. For some reason I don’t entirely understand I am considering trying the C25k – or rather, I tried it and discovered I am utterly, completely rubbish at running for reasons that impact (literally) my walking and posture. I have some interesting foot alignment issues that my sports massage person is working on, and the walk was intended to test some theories. And I needed to see some features in one of the parishes. So… would you like to come for a walk?

Here the cross-field path leaves the road. The stripes of bright autumnal colour mark places where glyphosate has been used to clear the path (cross-field paths are supposed to be clear ground for walkers), and to kill everything in a ‘sterile strip’ around the field margin. Striving to drive forward from the hips, powered by the glutes, with a mid-foot strike rolling to push off and up from the ball of my foot (instead of hammering my heels into the ground) I stride off, totally distracted by paying attention to my feet. Try it. I dare you.

Here the cross-field path leaves the road. The stripes of bright autumnal colour mark places where glyphosate has been used to clear the path (cross-field paths are supposed to be clear ground for walkers), and to kill everything in a ‘sterile strip’ around the field margin. Striving to drive forward from the hips, powered by the glutes, with a mid-foot strike rolling to push off and up from the ball of my foot (instead of hammering my heels into the ground) I stride off, totally distracted by paying attention to my feet. Try it. I dare you.

Another farm management photo. The crop is to the right, sterile strip just visible. There’s a ditch hidden in the trees and this wide uncropped field margin is intended to protect the water from agrochemicals, runoff and sediment washed down the field.

Another farm management photo. The crop is to the right, sterile strip just visible. There’s a ditch hidden in the trees and this wide uncropped field margin is intended to protect the water from agrochemicals, runoff and sediment washed down the field.

Eggshell fragments are scattered across the path. I don’t do egg ID; I thought these might be wood pigeon eggs, but those are white. What is interesting is the moisture around the eggs and the smear of yolk visible against the shell: these are signs that the eggs were broken open and the contents eaten, rather than dropped by one of the parents to clear out the nest. I doubt it was a mammalian predator – this is the middle of the field – so it was probably a bird that dropped the eggs to break open on impact. I’m guessing this because there were no signs of beak penetration or chipping away at fragments.

Eggshell fragments are scattered across the path. I don’t do egg ID; I thought these might be wood pigeon eggs, but those are white. What is interesting is the moisture around the eggs and the smear of yolk visible against the shell: these are signs that the eggs were broken open and the contents eaten, rather than dropped by one of the parents to clear out the nest. I doubt it was a mammalian predator – this is the middle of the field – so it was probably a bird that dropped the eggs to break open on impact. I’m guessing this because there were no signs of beak penetration or chipping away at fragments.

Spring Greens! Every year I enjoy watching the shades of green change, from the acid bright greens of spring to the deep glossy greens of high summer and, finally, the tired dusty brown-edged greens of late summer.

Spring Greens! Every year I enjoy watching the shades of green change, from the acid bright greens of spring to the deep glossy greens of high summer and, finally, the tired dusty brown-edged greens of late summer.

Lilac is one of the scents of my childhood summers. They were everywhere around the town where I grew up, but those I remember most clearly had gone wild in what were once the gardens of abandoned farmhouses hidden in the woods around the town. We were strictly forbidden to visit these places – tales were told of Bad Men, of concealed wells, of children who disappeared forever or, worse, reappeared as ghosts – but still we dropped our bikes on the roadside and explored the lilac-scented ruins on endless summer afternoons. Oh, and the building across the road is a traditional pub, the Pig and Abbot.

Lilac is one of the scents of my childhood summers. They were everywhere around the town where I grew up, but those I remember most clearly had gone wild in what were once the gardens of abandoned farmhouses hidden in the woods around the town. We were strictly forbidden to visit these places – tales were told of Bad Men, of concealed wells, of children who disappeared forever or, worse, reappeared as ghosts – but still we dropped our bikes on the roadside and explored the lilac-scented ruins on endless summer afternoons. Oh, and the building across the road is a traditional pub, the Pig and Abbot.

This is a view into the moat of a medieval moated manor, one of many I encountered on this walk. Tourist brochures suggest that moated manors are quaint or impressive half-timbered houses surrounded by a well-maintained rectangle of water, all set in beautiful lawns, but the majority are much less impressive unless you know what you’re seeing. Like this, many are completely overgrown by secondary woodland. Here’s an excerpt from Google Maps with moats marked in blue regardless of whether or not you can see anything on the ground. It was a very different landscape 500 and more years ago; the modern villages existed, but there were additional settlements – and these manors – outside the modern village boundaries. Note the village of Croydon at the top right, with moats to the north of it and a track leading south of the village to two more moats. Also, you may remember a walk to the Deserted Medieval Village of Clopton, which is the patch of green (with two more moats) across the road to the west of Croydon. Just to the right of that very dark field.

This is a view into the moat of a medieval moated manor, one of many I encountered on this walk. Tourist brochures suggest that moated manors are quaint or impressive half-timbered houses surrounded by a well-maintained rectangle of water, all set in beautiful lawns, but the majority are much less impressive unless you know what you’re seeing. Like this, many are completely overgrown by secondary woodland. Here’s an excerpt from Google Maps with moats marked in blue regardless of whether or not you can see anything on the ground. It was a very different landscape 500 and more years ago; the modern villages existed, but there were additional settlements – and these manors – outside the modern village boundaries. Note the village of Croydon at the top right, with moats to the north of it and a track leading south of the village to two more moats. Also, you may remember a walk to the Deserted Medieval Village of Clopton, which is the patch of green (with two more moats) across the road to the west of Croydon. Just to the right of that very dark field.

The path is marked by a tractor driven across an entire field of glyphosate autumn. I hate this: it’s spring, this should be green and full of life. But there is some life here; although there’s relatively little food available, sparsely vegetated ground is what some birds prefer for nesting. A lapwing was displaying to my right as I took this picture, so I tested the zoom to its limit…

The path is marked by a tractor driven across an entire field of glyphosate autumn. I hate this: it’s spring, this should be green and full of life. But there is some life here; although there’s relatively little food available, sparsely vegetated ground is what some birds prefer for nesting. A lapwing was displaying to my right as I took this picture, so I tested the zoom to its limit…

It’s just about in the centre of the image. Lapwings are wonderful birds. The individuals are pretty, but it’s the flocks I love best: their wings are largely black, but with large white patches on the underside. As the flocks swirl the white patches flash like laughter against sullen winter skies.

It’s just about in the centre of the image. Lapwings are wonderful birds. The individuals are pretty, but it’s the flocks I love best: their wings are largely black, but with large white patches on the underside. As the flocks swirl the white patches flash like laughter against sullen winter skies.

Looking back across the valley over the mound of the Bury, the moated manor at Clopton, with trees growing in the moat.

Looking back across the valley over the mound of the Bury, the moated manor at Clopton, with trees growing in the moat.

The car is usually parked in this gravel area when I walk to Clopton, but this time it’s nearly 7 miles away! The white objects seem to be junked refrigerators and freezers, possibly left to leak their refrigerants until they can be disposed of without paying for storage and disposal of freons. Grrrr. Cross the road and head down the High Street…

The car is usually parked in this gravel area when I walk to Clopton, but this time it’s nearly 7 miles away! The white objects seem to be junked refrigerators and freezers, possibly left to leak their refrigerants until they can be disposed of without paying for storage and disposal of freons. Grrrr. Cross the road and head down the High Street…

And find leafprints preserved in the thick paint marking the edge of the road! So well-made that it’s possible to identify the species – this is elm, with a serrated edge and asymmetrical base. For some reason I find this absolutely charming. Small things amuse small minds, perhaps :-)

And find leafprints preserved in the thick paint marking the edge of the road! So well-made that it’s possible to identify the species – this is elm, with a serrated edge and asymmetrical base. For some reason I find this absolutely charming. Small things amuse small minds, perhaps :-)

Croydon High Street on a quiet Saturday afternoon. It’s just the one road, lined with houses. A couple of footpaths run north between the houses and up the hill

Croydon High Street on a quiet Saturday afternoon. It’s just the one road, lined with houses. A couple of footpaths run north between the houses and up the hill

to one of the things I was hoping to find.

to one of the things I was hoping to find.

It doesn’t photograph at all well, but fortunately someone’s built a fence to show the undulations of the ridge and furrow of medieval arable preserved beneath this pasture. It’s a feature of medieval farming in this area, and farmers created it on purpose by ploughing their strips of land in the same direction year after year, with the plough shifting a little more soil from the hollow up toward the ridge every year. No one today is certain why this was done, but the usual theory is that it improved drainage on heavy soils: water ran down the ridges into the hollows.

It doesn’t photograph at all well, but fortunately someone’s built a fence to show the undulations of the ridge and furrow of medieval arable preserved beneath this pasture. It’s a feature of medieval farming in this area, and farmers created it on purpose by ploughing their strips of land in the same direction year after year, with the plough shifting a little more soil from the hollow up toward the ridge every year. No one today is certain why this was done, but the usual theory is that it improved drainage on heavy soils: water ran down the ridges into the hollows.

Here’s the mound of yet another moated manor house.

Here’s the mound of yet another moated manor house.

And, down the hill, this is All Saints, Croydon. A classic small church for a small village. The original nave, the main part of the church, is built using a wide variety of stones that would have been found in local fields – not a lot of money here in the 13th and 14th centuries. And perhaps they didn’t choose the best location or the best architect: one of several large brick buttresses is just visible between the entrance porch and the chapel, and those large black crosses on the tower are not windows, they’re the fixings for metal bars that run across the tower to stabilise it. The brick chancel was built in 1684, replacing the ruinous original.

And, down the hill, this is All Saints, Croydon. A classic small church for a small village. The original nave, the main part of the church, is built using a wide variety of stones that would have been found in local fields – not a lot of money here in the 13th and 14th centuries. And perhaps they didn’t choose the best location or the best architect: one of several large brick buttresses is just visible between the entrance porch and the chapel, and those large black crosses on the tower are not windows, they’re the fixings for metal bars that run across the tower to stabilise it. The brick chancel was built in 1684, replacing the ruinous original.

In the centre of the village I thought I could smell sheep, and there they were. The hillside behind them is the site of the medieval village of Croydon, now only earthworks, but (frustratingly) there is no public access.

In the centre of the village I thought I could smell sheep, and there they were. The hillside behind them is the site of the medieval village of Croydon, now only earthworks, but (frustratingly) there is no public access.

This is another of the things I came to see. The gate in the hedge marks the entrance to what in 1750 was Croydon Lane, running south from the village between the two moats I mentioned earlier.

This is another of the things I came to see. The gate in the hedge marks the entrance to what in 1750 was Croydon Lane, running south from the village between the two moats I mentioned earlier.

Today it’s just a footpath, but there are indications that it was once a more important route. It’s difficult to see in the photo, but the path is at least 18″ lower than the ground to either side, worn down by traffic over many years. I’d hoped for significant old trees on the banks beside it, or signs of traditional managment such as multi-stemmed trees growing from old coppice stools, but judging by the dense growth of young elms, the old trees may well have been elms that died of Dutch Elm Disease many years ago.

Today it’s just a footpath, but there are indications that it was once a more important route. It’s difficult to see in the photo, but the path is at least 18″ lower than the ground to either side, worn down by traffic over many years. I’d hoped for significant old trees on the banks beside it, or signs of traditional managment such as multi-stemmed trees growing from old coppice stools, but judging by the dense growth of young elms, the old trees may well have been elms that died of Dutch Elm Disease many years ago.

Here is what may be the remains of one giant, slowly returning to soil beside the path. My watch is sitting on the map to give some sense of scale.

Here is what may be the remains of one giant, slowly returning to soil beside the path. My watch is sitting on the map to give some sense of scale.

One of those two moats stood inside the ditched enclosure marked by trees in that photo. It’s also possible to see the height of the field surface compared to the track of Croydon Lane.

One of those two moats stood inside the ditched enclosure marked by trees in that photo. It’s also possible to see the height of the field surface compared to the track of Croydon Lane.

Croydon Lane originally continued straight ahead, across this field of Oil Seed Rape (canola to North Americans) to the line of trees (the footpath did, too, until relatively recently). The second moat would have stood to the right of the line of the Lane.

Croydon Lane originally continued straight ahead, across this field of Oil Seed Rape (canola to North Americans) to the line of trees (the footpath did, too, until relatively recently). The second moat would have stood to the right of the line of the Lane.

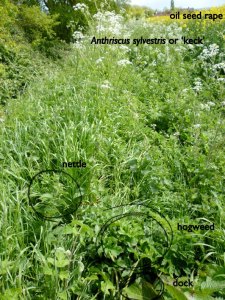

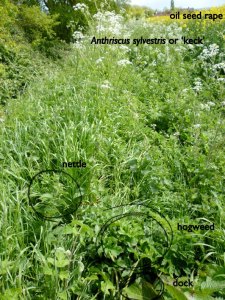

The path beside the trees is not walked frequently :-) Here’s a closer view of the vegetation:

The path beside the trees is not walked frequently :-) Here’s a closer view of the vegetation:

I was wearing shorts. The keck (that’s what my husband, born in Lincolnshire, uses as a generic term for all white umbellifers) is just a nuisance, but nettles sting and the sap of hogweed (Heracleum sphondylium) causes photosensitivity: it disables the skin’s response to sunlight, resulting in sunburn. It’s not nearly as bad as some of its relatives, such as Giant Hogweed and Cow Parsnip, but still… I walked carefully here.

I was wearing shorts. The keck (that’s what my husband, born in Lincolnshire, uses as a generic term for all white umbellifers) is just a nuisance, but nettles sting and the sap of hogweed (Heracleum sphondylium) causes photosensitivity: it disables the skin’s response to sunlight, resulting in sunburn. It’s not nearly as bad as some of its relatives, such as Giant Hogweed and Cow Parsnip, but still… I walked carefully here.

And then a mystery to occupy my mind for the rest of the walk (instead of fretting about how my feet were hitting the ground): there’s my watch on the ground in the middle of a field of field peas, next to something white.

And then a mystery to occupy my mind for the rest of the walk (instead of fretting about how my feet were hitting the ground): there’s my watch on the ground in the middle of a field of field peas, next to something white.

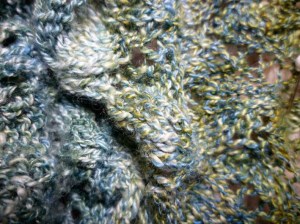

It’s a fragment of shell. A very waterworn fragment of shell, but it’s still got some sand cemented to it with what looks like white mud. In a pea field, full of silt and clay. Next to a stream, admittedly, but the stream is full of silt and clay and besides which, that thick large shell is from a saltwater mollusc. Why is it here? Perhaps it’s in some way related to the Roman villa site about 2 fields over. Or perhaps it’s much, much older, about 95 million years older, eroded out of a lump of chalk. That would explain the white mud. Debating the matter in my head occupied me nicely until the SMS discussion about whether or not he’d meet me at the pub about 15 minutes from home. In the event I opted for a shower first and after that I was too tired to move. Except to eat our well-deserved dinner!

It’s a fragment of shell. A very waterworn fragment of shell, but it’s still got some sand cemented to it with what looks like white mud. In a pea field, full of silt and clay. Next to a stream, admittedly, but the stream is full of silt and clay and besides which, that thick large shell is from a saltwater mollusc. Why is it here? Perhaps it’s in some way related to the Roman villa site about 2 fields over. Or perhaps it’s much, much older, about 95 million years older, eroded out of a lump of chalk. That would explain the white mud. Debating the matter in my head occupied me nicely until the SMS discussion about whether or not he’d meet me at the pub about 15 minutes from home. In the event I opted for a shower first and after that I was too tired to move. Except to eat our well-deserved dinner!

Have a picture of some fibre. It’s a promise: I have an entire post sitting in my head about how that became this

and why it’s much better than this:

But now it’s time for lunch.