We left our trusty sig vat on May 15th, hoping for a warm day that didn’t occur for another two days. But by the 17th the liquid was very definitely yellow-green although there was a lot of sediment and particulate matter adhering to the glass of the jar. I think this is a combination of vegetable and mineral matter in the indigo powder – the actual indigo content of ‘ordinary’ indigo may be well under 30% by weight – and some debris from the urine itself. At any rate, Sunday the 17th was forecast warm and sunny, so on Saturday I de-gummed 2 smallish skeins of handspun silk, neutralised the washing solution with a vinegar rinse, then rinsed them thoroughly to remove the vinegar, and left them soaking in water ready for dyeing. Remember that the soluble leuco-indigo needed to dye material converts to the insoluble, non-dyeing blue form in the presence of oxygen: it is generally advised that fibre be thoroughly wetted to minimise the amount of oxygen it introduces into the vat. If you’re dyeing in a urine vat, urine is the obvious fluid to use for wetting, as it adds nutrients for the fermentation.

Sunday morning I cracked open the lid of the jar in the greenhouse and the smell of the vat rose to greet me. A powerful aroma, now with some ammonia in the mix. I put both skeins in the jar, which on reflection was a bad move: there really wasn’t enough room for both. Also, as they were loose in the jar, they came into contact with the sediment.

My handspun silk in the urine vat in the greenhouse with the Japanese Indigo plants.

My handspun silk in the urine vat in the greenhouse with the Japanese Indigo plants.

I couldn’t wait to check whether it was working. Literally. The timestamp tells me this photo was taken only three minutes after the skeins went into the vat. How sad is that?

But look! It’s going blue! I pushed it back into the jar to go bluer.

I removed both skeins from the jar after 1.25 hours and hung them to dry on an improvised rack to oxidise. Note how turquoise the yarn appears at the beginning of the oxidation.

Now, at this point I digress to explain that throughout the afternoon my husband was walking back and forth from house to garage past the greenhouse and, eventually, the yarn from the vat. When he first encountered the smell of the vat he commented that it was a bit whiffy. I quickly shut the greenhouse to trap the odour. But by 1530, with the yarn out to oxidise, his comments were more forceful, along the lines of “The birds are falling dead from the trees!” The smell does fade from the dyed material; it’s much less noticeable when the material is dry, and I find that after washing with scented detergent and hanging to dry outside on the rosemary bush, I can only smell it if I press the fabric to my nose. The distinctive scent of the urine vat was once regarded as an indicator of good cloth well-dyed: when chemical vats were introduced in the second half of the 19th century, cloth-buyers would check for the smell of the urine vat. Some cloth merchants used commercially-available fake urine vat scent to mislead them!

As the oxidation proceeded I was able to see just how much gunge was stuck to the skeins, but could reassure myself that it will wash off (and it mostly did, even in the quick post-dyeing wash). I put the vat to bed (as it were), topping it up with fresh urine and replacing the bag of indigo.

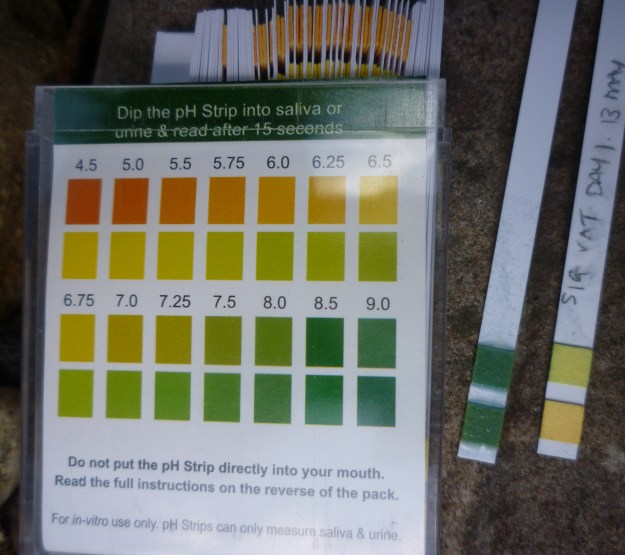

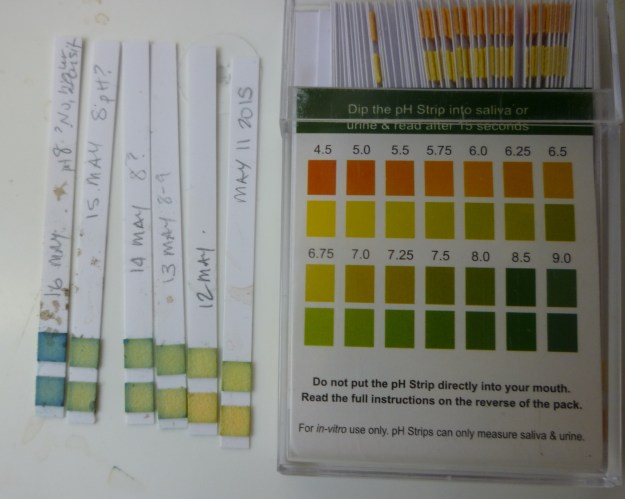

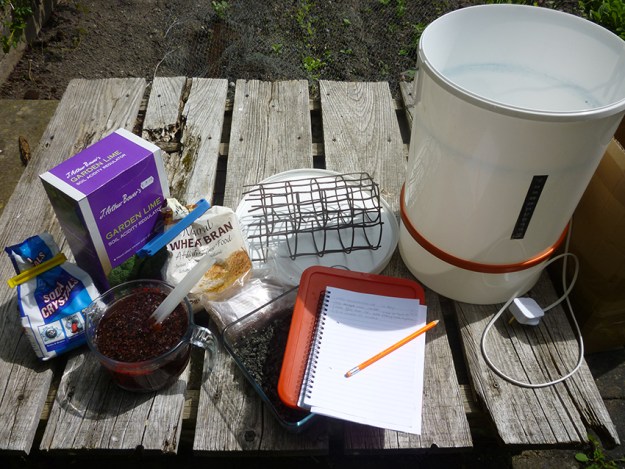

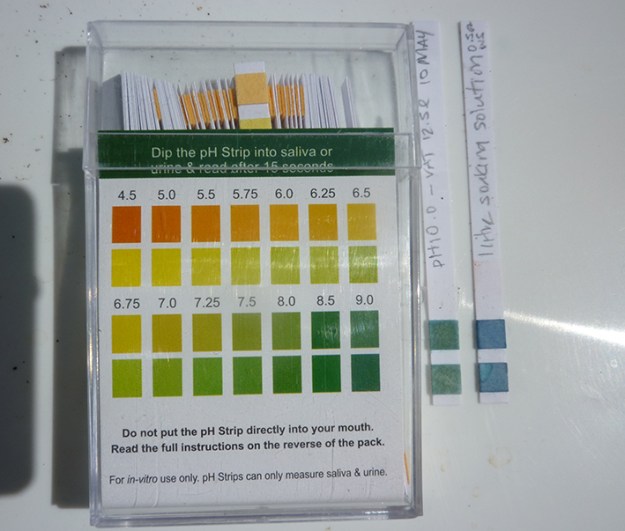

Once washed and dried the skeins proved paler than I’d hoped, so I tested one of the characteristics of the urine vat. With pH paper. Most indigo vats are strongly alkaline (my post on Indigo chemistry explains why), running at pH11 or even higher. This alkalinity degrades and damages protein fibres such as silk, so repeated or lengthy dips to get greater depth of colour are a bad idea. The urine vat, however, is much less alkaline: this one, yellow-green and ready to dye, tested pH9 on the 24th May. I decided to see what happened if I put a dry skein of silk for a longer period (dry because I had read that putting the fibre in dry could give a greater depth of colour). I pushed a skein into the jar late in the afternoon, took it out to oxidise for a couple of hours in the early evening – it was noticeably darker – and then replaced it in the jar overnight. End result: a significantly darker indigo.

It’s still a little bit turquoise, but obviously much darker than the skein next to it. Which is in fact a bit darker than it looks in the photo: light reflecting off the silk makes it paler.

Conclusions

Pros: This is the easiest and least expensive of the vats I’ve tried so far (more than I’ve written about so far), and it’s kinder to protein fibres such as silk and wool than the other vats. The results are good, but I think they’ll be better in a different vat. I think a higher grade of indigo (containing less waste material) will give me darker colours, and a larger, deeper vat will make it possible to avoid any sediment, perhaps by placing something like a colander or strainer at the bottom of the vat to keep the material off the bottom. So I’ve ordered a better grade of indigo and I’m about to start collecting more urine.

Cons: This vat has a strong, distinctive, and – to some people at least – highly unpleasant odour. While the odour from the vat can be controlled and contained, the smell coming off the dyed material as it oxidises is less easy to contain if it’s hung out to air. However, it is possible to oxidise the dyed material in well-oxygenated water: allow the cold water (cold water holds more oxygen than hot) to plunge into a container in such a way as to generate lots of aeration bubbles. Immerse the fabric in that water, swirl it around, keep the tap running to refresh the oxygen. This is not a technique to use with warm wool, but I have tried it with silk and found no damage, although the skein could have done with more ties. In theory it should not remove indigo that wouldn’t be lost in the normal washing process, but I have no real way to test that theory at the moment.