Are you sitting comfortably? Then I’ll begin.

A long time ago, at a Medieval Textiles conference in London in 2011, I was held spellbound by Anna Nørgård talking about spinning and weaving sails for the reconstructed Viking Age ships at Roskilde. I took copious notes – I still have them on file – and clearly remember purposefully forging through the crowd to handle the samples of yarn and sailcloth, as it came off the loom and after waterproofing with fat from whatever animals had died recently. I promised myself that one day I would go to the Roskilde Vikingeskibsmuseet and see the woollen sails on the ships.

The timing of this entire holiday was determined about 6 months ago by the availability of evening cruises on the fjord (in reality a large brackish waterbody, no cliffs. This is Denmark, not Norway) in vessels built at the Skibsmuseet, plus A Birthday date.

The twin pointy things visible over the rooftops are two spires of Roskilde Cathedral.

The twin pointy things visible over the rooftops are two spires of Roskilde Cathedral.

So at long last on Thursday morning we walked north to Nørreport for the train to Roskilde.There is more to see here: Roskilde Cathedral is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the first Gothic cathedral in Scandinavia, the first Gothic cathedral built of brick, and the burial place of Danish monarchs since the 15th century.

It’s impressive. Very impressive. Strangely approachable, almost homely in warm red brick by comparison with the more usual cold grey stone. Someone was practising on the organ (the oldest parts of which date from 1555).

Medieval wall paintings cover some of the chapels. Those in St Birgitta’s chapel date from the early 1500s.

The main theme, though, is the death of Danish monarchs. There’s a good summary here with photos, albeit not English text.

The chapel containing the monuments to Christian 9 and Louise, Christian 10 and Alexandrine, and Frederik 9 and Ingrid is stunning in its relative simplicity. Tombs of grey granites and marbles and white marble statues (the ‘three sisters of the Little Mermaid’: Grief, Memory and Love. The sculptor Edvard Eriksen’s wife was the model for all four) are bathed in light from the dome, reflecting off the white walls. It’s Northern and beautiful, and too busy for a photo while we were there.

The chapel of Frederic 5 has a similar feel but the neo-classicist style is more ornate.

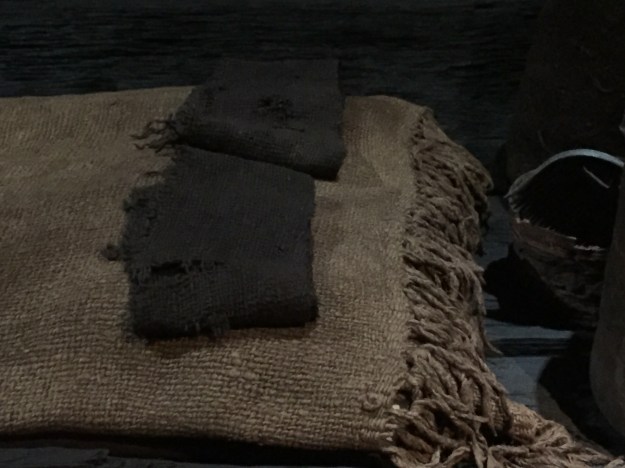

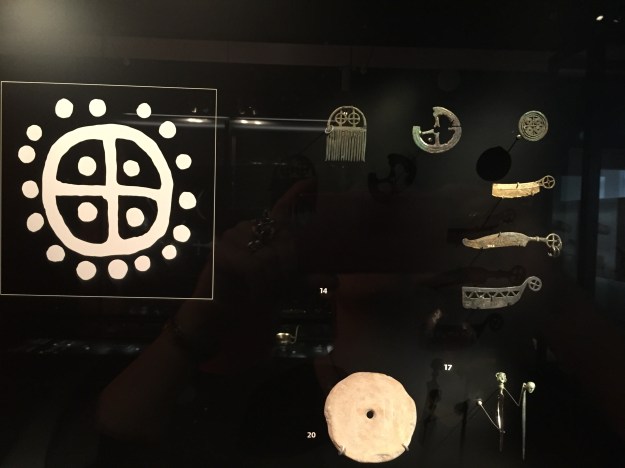

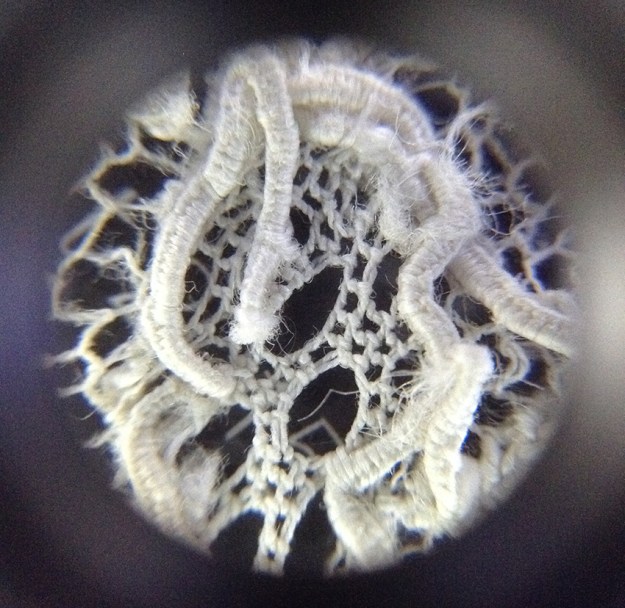

I was rather taken by the use of dead blacke velvet to cover some of the coffins. Intending no disrespect to Juliana Maria, my eye was caught by some of the gold trim … It looks very like brocaded tablet weaving.

Christian 1’s chapel is also richly painted with frescoes from the second half of the 1400s.

Follow the signs, walk down the hill to the harbor, and we’re there.

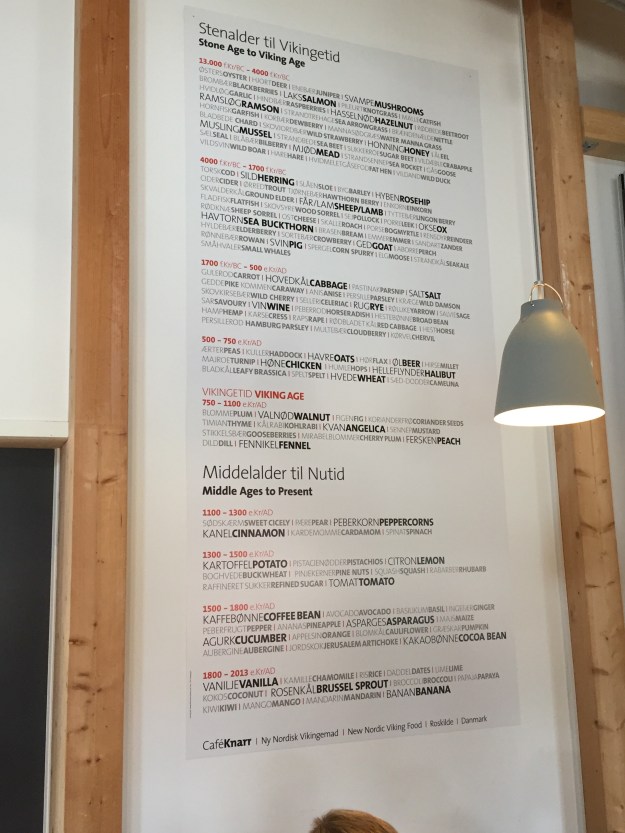

The café serves good food and information

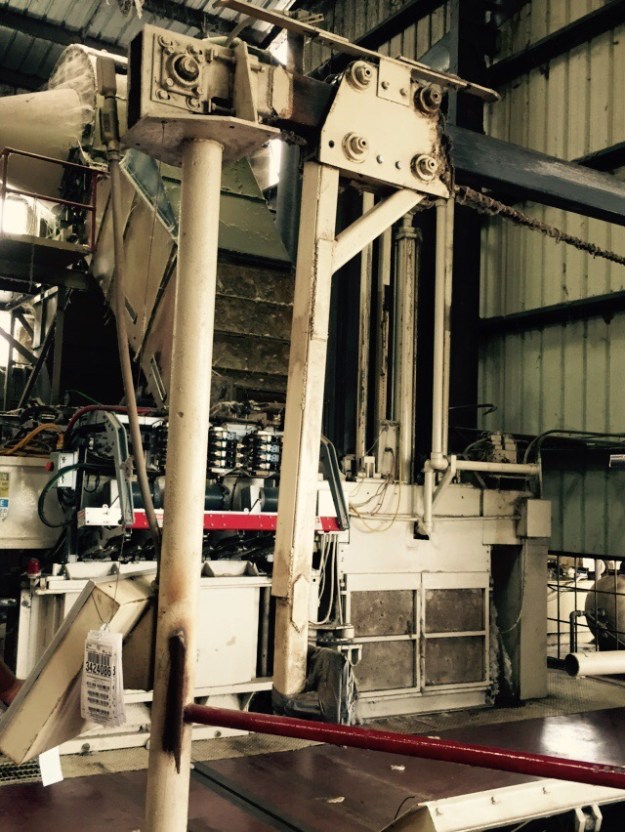

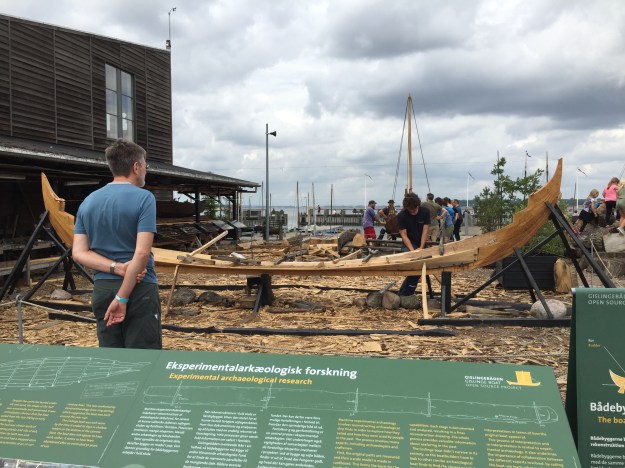

While we waited for our lunch (it had been a long morning and would be a longer evening), i bounced around the workshops in the yard. Especially this one: the rope maker. He was at lunch, but the materials – and a counter covered with sample ropes were there to be admired. Look closely at the cones of hemp yarn visible at right: that’s the last stock of hemp yarn tight-spun for ropemaking in the world. If they want more they’ll have to commission it, and the minimum order is enough to rig an entire ship larger than any Roskilde have.

In addition to the ‘Viking’ boats, the ship museum builds and maintains a collection of traditional working boats. They’re building another take of the Gislinge boat, a working boat from c. 1130. She should be ready for the water some time in November 2016.

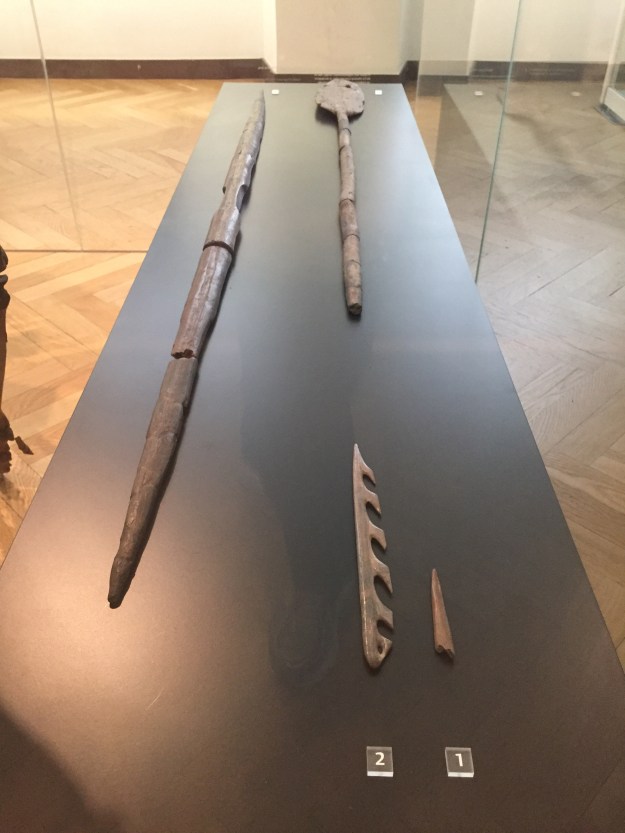

Early log boats (hollowed trees) were enlarged by adding boards to raise the side, sewn together with fir or spruce roots, or lime bast.

The rope maker was back! We talked about lime bast vs seal hide, and he showed me how to make rope from bast. I’ve studied Youtube to no avail, but now I think i understand.

It’s more wrap than twist, although there is twist. The winder is used to add a little more twist.

Starting the loop at one end of the rope. Each piece of bast rope is made to order, a specific length, with the ends finished in a specific way.

Starting the loop at one end of the rope. Each piece of bast rope is made to order, a specific length, with the ends finished in a specific way.

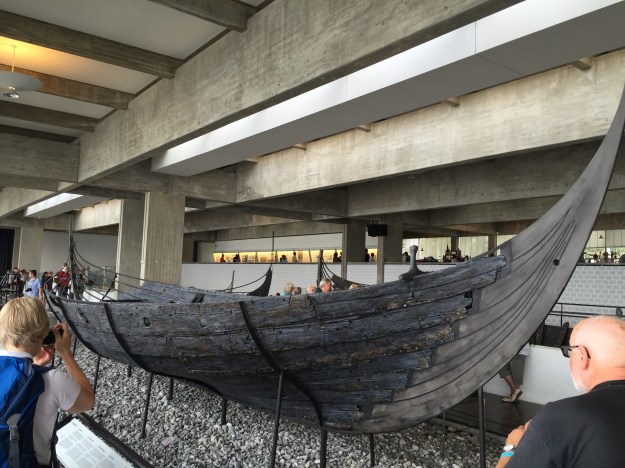

I spent ages watching and asking questions before i took my leave and we headed into what is for most people the main event: the building housing the restored original Viking boats.

A 1:10 model of one of the boats, used to work out the principles before planning the full-size replica.

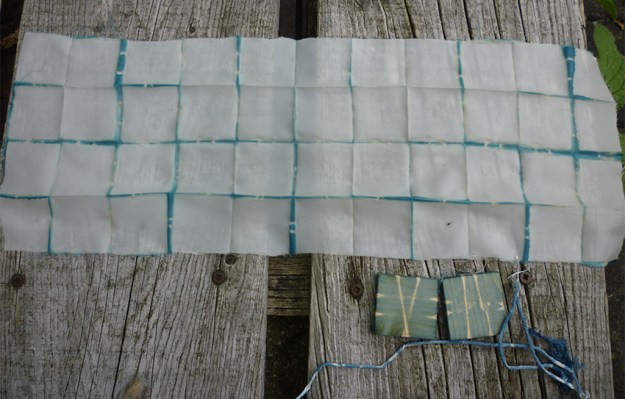

Down the far end, in good light, we saw a warp-weighted loom of linen yarn and someone sewing: Anna making linen ‘summer’ sails for the 2016 Gislinge boat.

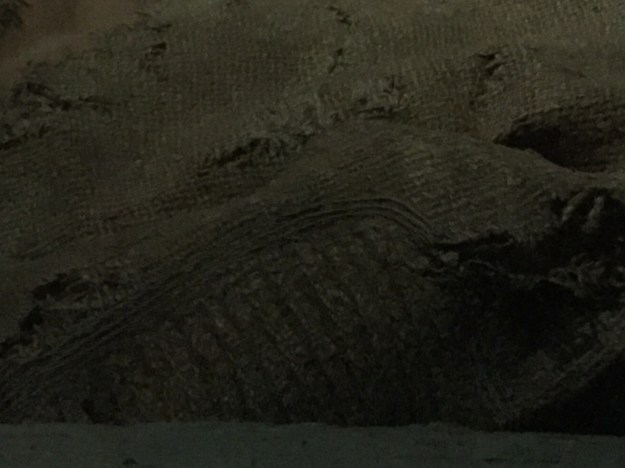

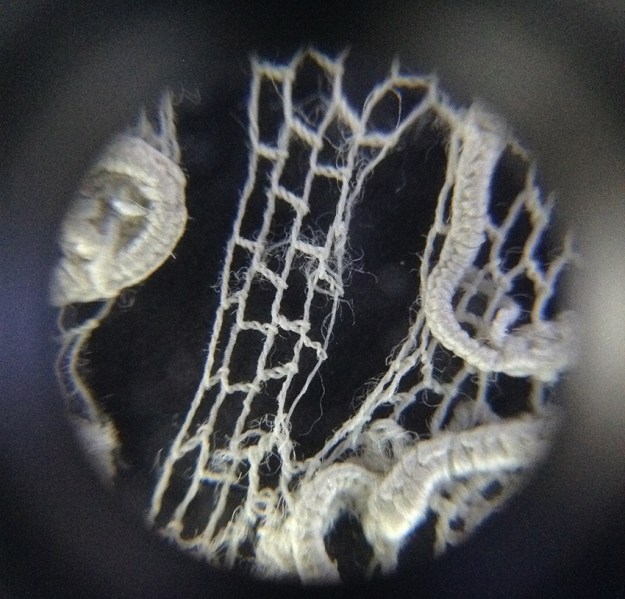

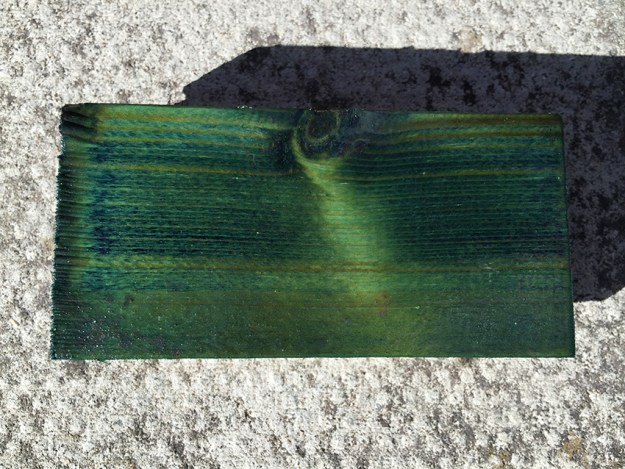

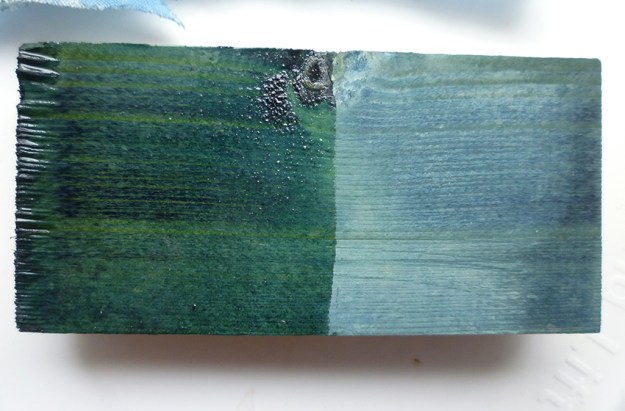

We talked about nettle and linen and the Must Farm finds, and then it was time to go and wait for the evening cruise. Not in fact one of the big and rather temperamental Viking boats, but a replica Norwegian working boat – with a hand-woven, hand-sewn greased woollen sail. Not hand-spun: it would take too long for one spinner who also has to weave! Anna spun samples that were sent to the mill. I don’t have many photos: I was a little reluctant to have my phone out while we were on the water.

Apparently this is an old sail, wearing thin, so the wind goes through it more than it should. It catches more wind when freshly dressed, but people in the boat object to melted grease dripping from the sail in hot weather.

Apparently this is an old sail, wearing thin, so the wind goes through it more than it should. It catches more wind when freshly dressed, but people in the boat object to melted grease dripping from the sail in hot weather.

We rowed out of the harbour (i like rowing, except for the person behind me who couldn’t keep stroke) until we caught the wind and could raise the sail. We sailed out, around the island and back; tacking was required. A. had the tiller for most of the journey back and was told he’d done very well fir someone who’d never sailed before. It’s not easy trying to keep the wind in the sail AND the boat making progress to the harbour. Then we rowed back into the harbour and i still liked it, except for the same person behind me.

And then we walked to the station and caught the train back to Copenhagen. 2300 hours was a long day of fun.